The U.S. Has Billions for Wind and Solar Projects. Good Luck Plugging Them In.

Author: Brad Plumer

Wind and Solar Projects

An explosion in proposed clean energy ventures has overwhelmed the system for connecting new power sources to homes and businesses.

Plans to install 3,000 acres of solar panels in Kentucky and Virginia are delayed for years. Wind farms in Minnesota and North Dakota have been abruptly canceled. And programs to encourage Massachusetts and Maine residents to adopt solar power are faltering.

The energy transition poised for takeoff in the United States amid record investment in wind, solar and other low-carbon technologies is facing a serious obstacle: The volume of projects has overwhelmed the nation’s antiquated systems to connect new sources of electricity to homes and businesses.

More than [8,100 energy projects](https://emp.lbl.gov/queues) — the vast majority of them wind, solar and batteries — were waiting for permission to connect to electric grids at the end of 2021, up from 5,600 the year before, jamming the system known as interconnection.

PJM Interconnection, which operates the nation’s largest regional grid, stretching from Illinois to New Jersey, has been so inundated by connection requests that last year it [announced a freeze on new applications](https://insidelines.pjm.com/ferc-approves-interconnection-process-reform-plan/) until 2026, so that it can work through a backlog of thousands of proposals, mostly for renewable energy.

Fewer than one-fifth of solar and wind proposals actually make it through the so-called interconnection queue, [according to research](https://emp.lbl.gov/news/record-amounts-zero-carbon-electricity) from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The landmark climate bill he signed last year [provides $370 billion in subsidies](https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/08/02/climate/manchin-deal-emissions-cuts.html) to help make low-carbon energy technologies — like wind, solar, nuclear or batteries — cheaper than fossil fuels.

But the law does little to address many practical barriers to building clean energy projects, such as [permitting holdups](https://thebulletin.org/2023/02/cutting-the-red-tape-for-cleaner-energy-the-pros-and-cons-of-permitting-reform/), [local opposition](https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/30/climate/wind-farm-renewable-energy-fight.html) or transmission constraints. Unless those obstacles get resolved, experts say, there’s a risk that billions in federal subsidies won’t translate into the deep emissions cuts envisioned by lawmakers.

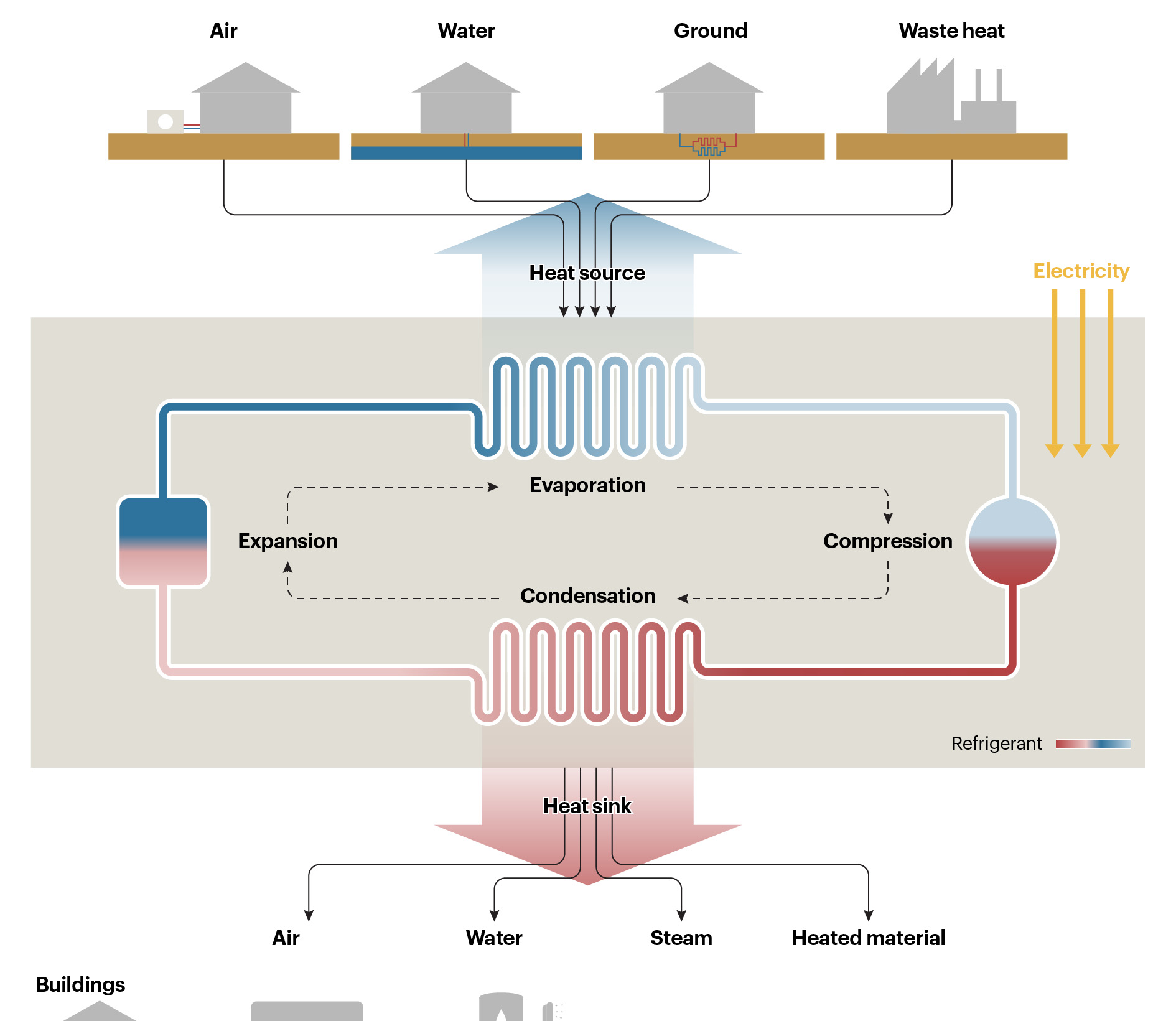

A potentially bigger problem for solar and wind is that, in many places around the country, the local grid is clogged, unable to absorb more power.

That means if a developer wants to build a new wind farm, it might have to pay not just for a simple connecting line, but also for deeper grid upgrades elsewhere.

These costs can be unpredictable. In 2018, EDP North America, a renewable energy developer, proposed a 100-megawatt wind farm in southwestern Minnesota, estimating it would have to spend $10 million connecting to the grid. But after the grid operator completed its analysis, EDP learned the upgrades would cost $80 million. It canceled the project.

A better approach, Mr. Gramlich said, would be for grid operators to plan transmission upgrades that are broadly beneficial and spread the costs among a wider set of energy providers and users, rather than having individual developers fix the grid bit by bit, through a chaotic process.

As grid delays pile up, regulators have taken notice. Last year, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission proposed two major reforms to [streamline interconnection queues](https://www.ferc.gov/news-events/news/ferc-proposes-interconnection-reforms-address-queue-backlogs) and encourage grid operators to [do more long-term planning](https://www.ferc.gov/news-events/news/ferc-issues-transmission-nopr-addressing-planning-cost-allocation).

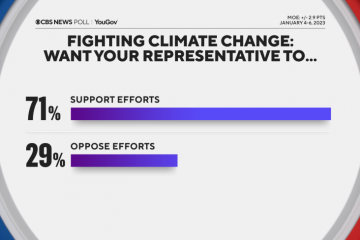

If the United States can’t fix its grid problems, it could struggle to tackle climate change. Researchers at the Princeton-led REPEAT project [recently estimated](https://repeatproject.org/docs/REPEAT_IRA_Transmission_2022-09-22.pdf) that new federal subsidies for clean energy could cut electricity emissions in half by 2030. But that assumes transmission capacity expands twice as fast over the next decade. If that doesn’t happen, the researchers found, emissions could actually increase as solar and wind get stymied and existing gas and coal plants run more often to power electric cars.