In 1992, the first text message was sent. After a slow start, text-based services exploded. Today, over 23 billion messages are sent every single day. This paved the way for the smartphone revolution that we have seen today. And other technology trends have followed that same curve.

I know how much we struggle to comprehend and predict what “exponential change” means. Because I was at Nokia in 1993 when that technological revolution started. And now as head of UN Climate Change, I’m here to tell you that what was true for mobile phones back in 1992, and other revolutionary shifts, is also true for climate action today.

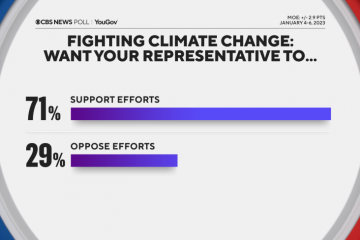

To make climate action go from linear to exponential pace, it’s not just my job to make it happen. It’s also your job, too. We all know that climate impacts are hitting harder and harder every day. The ambition we need to see, reducing emissions, adapting to impacts and providing the means to address the crisis, are severely lacking. But just like technology, public opinion has its tipping point.

In my youth, I campaigned against apartheid. Participating in that fight, those demonstrations, meant shaking the foundations of a system many thought would never change. But then, one day, after generations of slow progress, the system changed. The pressure was too great. The point tipped.

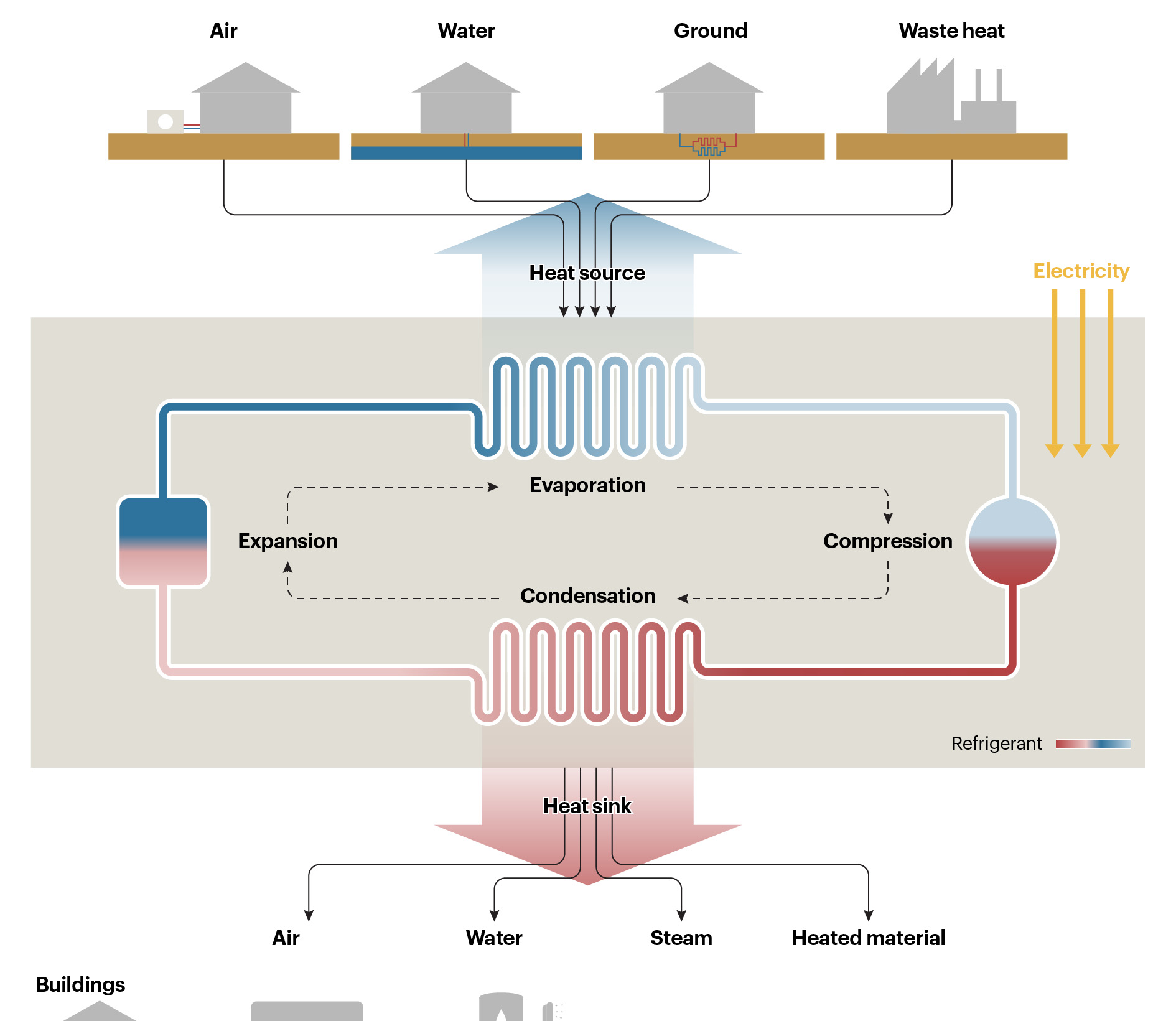

We’re here in Detroit, the heart of car manufacturing. Take a look at this graph. Electric vehicle sales are expected to increase to become 70 percent by 2030. Another example. Solar energy. Between 2010 and 2020, we moved from 20 gigawatts of solar energy installed to 150 gigawatts. Now, just three years later, that number is expected to increase to 350 gigawatts per year. And by 2030, that number is expected to increase again to 1,000 gigawatts per year.

Change can come fast. But time isn’t on our side. We have less than seven years between now and 2030 to halve our global emissions. So the question is: Will those tipping points come soon enough to avoid the catastrophic impacts of climate change?

At out current speed, change will come too late to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. That is the hard truth of the global stocktake that will be completed by the UNFCCC this year.

But this is where you come in. You may think it’s not your responsibility to drive change. You may not think you have the power to make this happen. Both of those statements are wrong.

At the UNFCCC, we are the custodians of the process. We’re the defenders of the agreements. We are the champions of parties and the agreements that they make. But globally, we’re collectively in a state of what the author Kim Stanley Robinson describes as “The Dithering.” A state of indecision and a state of inaction in the face of a global crisis. But countries will agree to boost in action. If enough people encourage them to do so. Contact your representatives and ask them what they are doing to deliver. What plans do they have to ensure that your concerns on climate count? That direct action does work.

I have seen positions change time and time again when citizens engage directly. Every time you buy something, ask yourself the question: Is this the greenest option? Ask those around you about their green choices. Learn new things. Educate and mobilize. The power of human organization can result in change.

Which brings me to my final point. You don’t have to be a politician or a prominent business person to make a significant contribution. Climate action calls for all skill sets. Ask yourself: What am I passionate about? What am I good at? What am I training for? Then ask yourself the question, how can I apply this to the climate crisis? And do exactly that thing.

If you act, the exponential change that is needed will happen. I thank you.