Politics

Trump Makes Clear His Opposition to More Money to Support Mail Voting

By Emily Cochrane and Aug. 13, 2020

Democrats are alarmed that the president is seeking to undercut the election and sow confusion about the outcome.

The appointment as postmaster general in May of Louis DeJoy, a Trump campaign contributor with significant financial interests in the Postal Service’s competitors and contractors, has prompted further concerns about the politicization of the agency, particularly after Mr. DeJoy put in place policy changes that have slowed mail delivery in some areas.

Mr. DeJoy has kept tens of millions of dollars invested in XPO Logistics, a Postal Service contractor for which he was a board member, first reported by CNN on Wednesday. However, he sold his stake in United Parcel Service, a major rival for the post office, in June, according to financial disclosures.

Shortly after he divested between $100,000 and $250,000 in Amazon stock the same month, he bought $50,000 to $100,000 in stock options for the company. Amazon, a frequent subject of Mr. Trump’s attacks, is a major competitor to the Postal Service in package delivery.

Former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., called it a cynical attempt at disenfranchisement.

“The president of the United States is sabotaging a basic service that hundreds of millions of people rely upon, cutting a critical lifeline for rural economies and for delivery of medicines, because he wants to deprive Americans of their fundamental right to vote safely during the most catastrophic public health crisis in over 100 years,” said Andrew Bates, a spokesman for the Biden campaign.

Voting activists said that Mr. Trump’s remarks simply made clear what they already suspected: that the president was attacking the post office to undermine the election. Tammy Patrick, an expert on mail-in voting and senior adviser at the Democracy Fund, a nonpartisan grant-making foundation, maintained that funding was not intended to implement a “universal vote by mail,” as the president put it, but rather a secure option for voters amid the pandemic.

Wendy Weiser, the director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice, a New York-based research organization, said Mr. Trump’s comments effectively throw “the ball into Congress’s court” to provide the necessary money. Any funding bill, however, would require Mr. Trump’s signature to become law.

Democrats have pushed to infuse at least $2 trillion into the American economy and include money for state and local governments, food assistance programs and for election security and the Postal Service.

In addition to new funding for the Postal Service, Ms. Pelosi and Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the Democratic leader, have called for legislative language that would counter some of the operational changes Mr. DeJoy has instituted.

At least one Republican has also expressed support for providing some additional money to the agency.

“I do disagree with the president on the need to support the Postal Service,” said Senator Susan Collins of Maine, one of a number of vulnerable Republicans up for re-election in November.

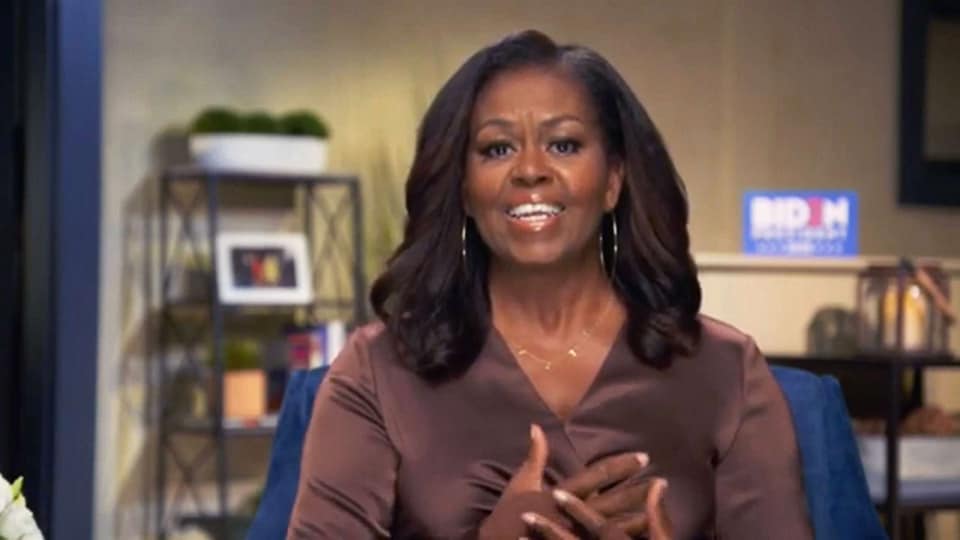

holocaust

Memory Forward: How the 3rd Generation tells the stories of the Holocaust

Grandchildren of Holocaust Survivors from around the world discuss how they are carrying the memory of the Holocaust into the future.

Rachael Cerrotti (USA) is a 3rd generation descendant, an award-winning multidisciplinary storyteller and educator. Her work explores the intergenerational impact of migration and memory.

Rachael has been published and featured by NPR, PRI’s The World, Kind World, WBUR, WGBH, The Boston Globe, Images & Voices of Hope, The Times of Israel and various other publications throughout Israel, Europe and the United States. In 2019, she released her first podcast — We Share The Same Sky — which was produced for USC Shoah Foundation and tells the story of her decade-long journey to retrace her grandmother’s war story. Her forthcoming memoir will be published in Fall of 2021.

Rachael holds a degree in Communications from Temple University and is an alumni of The Rothberg International School at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Rachael has completed educator’s seminars with Yad Vashem and Facing History & Ourselves, and has worked in over a dozen countries.

Ricki Gurwitz (Canada) is a former producer at CTV News Channel. She started her career in New York, where she was a producer at WABC News Talk Radio. She moved back to Toronto in 2009, and took over the production of The Bill Carroll Show and The Jerry Agar Show on Newstalk 1010. In 2011, Ricki made the switch to television, joining CTV News Channel as a segment and associate producer.

In 2015, Ricki left CTV to produce The Accountant of Auschwitz, her first feature documentary. In 2015, 94-year-old former German SS officer Oskar Gröning, nicknamed “the accountant of Auschwitz” was charged with complicity in the murder of 300,000 Jews at Auschwitz in 1944. The trial made headlines around the world as a frail old man took the stand to face his former victims. Gröning’s trial reflects not only one frail bookkeeper’s penitence, but the world’s responsibility to hold the worst of human horrors forever to public view.

Currently, Ricki is a producer at the Munk Debates, the world’s largest public debate forum.

Dr. Liat Steir-Livny (Israel) is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Culture at Sapir Academic College, and a tutor and course coordinator for the Open University of Israel’s Cultural Studies MA program and the Department of Literature, Language, and the Arts. Liat’s research focuses on Holocaust commemoration in Israel.

Liat is the recipient of the 2019 Young Scholar Award given jointly by the Association for Israel Studies (AIS) and the Israel Institute. She is also the author of five books:Two Faces in the Mirror analyzes the representation of Holocaust survivors in Israeli cinema; Let the Memorial Hill Remember discusses the changing memory of the Holocaust in contemporary Israeli culture; Is it O.K to Laugh about it? analyzes Holocaust humor, satire and parody in Israeli culture; Three Years, Two Perspectives, One Trauma analyses the media of prominent Jewish organizations in the USA and Eretz-Israel after WWII; and Remaking Holocaust Memory analyses documentary Cinema by 3G descendants in Israel.

Cayle White (USA) of 3GNY will moderate this webinar. Cayle is the granddaughter of two Holocaust Survivors from Poland. She grew up in Toronto, Canada, and moved to New York City to pursue her Liberal Arts degree at New York University.

Cayle is a board member of 3G New York, committee member of the Holocaust Committee of the Abraham Joshua Heschel School, Moth storyteller, stage performer, public speaker for NYC middle and high school students, and educational consultant and admissions coach for special needs and Jewish Day schools. Cayle and her network of experts, therapists, evaluators and educators work with students from preschool through high school.

Cayle was also the associate-producer of Kensington: A Past Without a Future, a documentary about the Jewish immigrant quarter of Toronto, and the writer, director and narrator of the documentary Poor but Stupid, which earned her a National Film Board of Canada honorable mention in 2002.

Politics

Postmaster General Louis DeJoy must be removed from office to save our democracy!

Postmaster General Louis DeJoy must be removed from office to save our democracy! Louis DeJoy — a major GOP donor to President Donald Trump has issued a sweeping overhaul of the US Postal Service, including the ouster of top executives from key posts and the reshuffling of more than two dozen other officials and operational managers. This is a direct effort by DeJoy to exploit his authority at the Postal Service to further the president’s political interests and reelection prospects.

The postal service lies at the heart of our democracy and is critical to the success of an unprecedented vote-by-mail system that is needed for a fair and effective 2020 election season. The postal service helps ensure that our nation’s most vulnerable communities are receiving medications and resources during the pandemic.

In 2016 and 2018, close to 40 percent of Americans voted by mail. That could almost double this fall with the pandemic concerns. States run elections, but the Postal Service is central to mail voting.

Trump administration’s intentions are clear: DeJoy, a Trump donor with no experience inside the postal service, has been installed to cause chaos and disruption at a time when the timely delivery of mail could not be more critical.

holocaust

The Legal Right to Protest in The U. S.

ARRESTING DISSENT: LEGISLATIVE RESTRICTIONS ON THE RIGHT TO PROTEST, PEN AMERICA May 2020

The right to protest is a fundamental constitutional right in the U.S., arising from the First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom to petition the government. While these rights are subject to some government regulation for preservation of public safety, order, and peace, they are generally carefully guarded from government interference and regarded as essential components of democracy.

The First Amendment explicitly lays out that Congress—and, by extension under the Fourteenth Amendment, state governments— shall make no law abridging or limiting our right to assemble or speak freely. While these protections have been tested time and again throughout our country’s history, the result has been a long history of jurisprudence repeatedly re-affirming both the civic importance of, and the legal right to, public protest. “The tradition of public protest dates back to the revolutionary period,” First Amendment lawyer Bob Corn-Revere of Davis Wright Tremaine told PEN America. “And it gained judicial recognition in the 20th century as the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment requires the government to preserve the right to speak in public spaces.” In 1939, the Supreme Court recognized that “[u]se of the streets in public places has, from ancient times, been part of the privileges, immunities, rights and liberties of citizens.” Streets, parks, and sidewalks have “immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly.” By 1949, the Supreme Court acknowledged that protected speech “may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.”

While it is true that the government may impose some regulations on the right to assemble, these regulations must be narrowly circumscribed. Government actors have latitude to regulate the time, place, and manner (“TPM”) of protest and other expressive activity, so long as such restrictions are: content-neutral; narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest; and leave open ample alternatives for communication. Similarly, the Supreme Court has long made it clear that the government can only impose restrictions on the exercise of speech when such restrictions are “‘reasonable and […] not an effort to suppress expression merely because public officials oppose the speaker’s view.’”

The government does have some limited power to act to disallow or shut down assemblies that pose a risk to public order, including there being the clear and present danger of imminent collective violence. Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe’s declaration of an “unlawful assembly” during the Unite the Right white supremacist rally in Charlottesville in 2017, stands as an example of such permissible power. Even in such instances, these powers are circumscribed by the First Amendment, and rely on the finding of an imminent threat to public safety.

At times throughout history, some protests have employed civil disobedience—a form of protest that includes the willful decision to disobey the law but which is in practice predominantly nonviolent— as a form of activism and for the attention these acts often garner. While such actions, by virtue of their illegality, are not protected by the First Amendment, nonviolent civil disobedience has often been effective in achieving social change, including the realization or enlargement of our human and civil rights. Furthermore, civil disobedience is predominantly a non-violent act; most definitions of civil disobedience specifically exclude acts of violence. This distinction, between non-violent civil disobedience and acts of violence, is often conveniently elided by authorities who wish to paint participants in civil disobedience with the same broad brush as violent actors.

holocaust

Elie Wiesel – The Perils of Indifference

Speech Delivered April 12, 1999, Washington, D.C.

Audio of address:

Mr. President, Mrs. Clinton, members of Congress, Ambassador Holbrooke, Excellencies, friends:

Fifty-four years ago to the day, a young Jewish boy from a small town in the Carpathian Mountains woke up, not far from Goethe’s beloved Weimar, in a place of eternal infamy called Buchenwald. He was finally free, but there was no joy in his heart. He thought there never would be again. Liberated a day earlier by American soldiers, he remembers their rage at what they saw. And even if he lives to be a very old man, he will always be grateful to them for that rage, and also for their compassion. Though he did not understand their language, their eyes told him what he needed to know — that they, too, would remember, and bear witness.

And now, I stand before you, Mr. President — Commander-in-Chief of the army that freed me, and tens of thousands of others — and I am filled with a profound and abiding gratitude to the American people. “Gratitude” is a word that I cherish. Gratitude is what defines the humanity of the human being. And I am grateful to you, Hillary, or Mrs. Clinton, for what you said, and for what you are doing for children in the world, for the homeless, for the victims of injustice, the victims of destiny and society. And I thank all of you for being here.

We are on the threshold of a new century, a new millennium. What will the legacy of this vanishing century be? How will it be remembered in the new millennium? Surely it will be judged, and judged severely, in both moral and metaphysical terms. These failures have cast a dark shadow over humanity: two World Wars, countless civil wars, the senseless chain of assassinations (Gandhi, the Kennedys, Martin Luther King, Sadat, Rabin), bloodbaths in Cambodia and Algeria, India and Pakistan, Ireland and Rwanda, Eritrea and Ethiopia, Sarajevo and Kosovo; the inhumanity in the gulag and the tragedy of Hiroshima. And, on a different level, of course, Auschwitz and Treblinka. So much violence; so much indifference.

What is indifference? Etymologically, the word means “no difference.” A strange and unnatural state in which the lines blur between light and darkness, dusk and dawn, crime and punishment, cruelty and compassion, good and evil. What are its courses and inescapable consequences? Is it a philosophy? Is there a philosophy of indifference conceivable? Can one possibly view indifference as a virtue? Is it necessary at times to practice it simply to keep one’s sanity, live normally, enjoy a fine meal and a glass of wine, as the world around us experiences harrowing upheavals?

Of course, indifference can be tempting — more than that, seductive. It is so much easier to look away from victims. It is so much easier to avoid such rude interruptions to our work, our dreams, our hopes. It is, after all, awkward, troublesome, to be involved in another person’s pain and despair. Yet, for the person who is indifferent, his or her neighbor are of no consequence. And, therefore, their lives are meaningless. Their hidden or even visible anguish is of no interest. Indifference reduces the Other to an abstraction.

Over there, behind the black gates of Auschwitz, the most tragic of all prisoners were the “Muselmanner,” as they were called. Wrapped in their torn blankets, they would sit or lie on the ground, staring vacantly into space, unaware of who or where they were — strangers to their surroundings. They no longer felt pain, hunger, thirst. They feared nothing. They felt nothing. They were dead and did not know it.

Rooted in our tradition, some of us felt that to be abandoned by humanity then was not the ultimate. We felt that to be abandoned by God was worse than to be punished by Him. Better an unjust God than an indifferent one. For us to be ignored by God was a harsher punishment than to be a victim of His anger. Man can live far from God — not outside God. God is wherever we are. Even in suffering? Even in suffering.

In a way, to be indifferent to that suffering is what makes the human being inhuman. Indifference, after all, is more dangerous than anger and hatred. Anger can at times be creative. One writes a great poem, a great symphony. One does something special for the sake of humanity because one is angry at the injustice that one witnesses. But indifference is never creative. Even hatred at times may elicit a response. You fight it. You denounce it. You disarm it.

Indifference elicits no response. Indifference is not a response. Indifference is not a beginning; it is an end. And, therefore, indifference is always the friend of the enemy, for it benefits the aggressor — never his victim, whose pain is magnified when he or she feels forgotten. The political prisoner in his cell, the hungry children, the homeless refugees — not to respond to their plight, not to relieve their solitude by offering them a spark of hope is to exile them from human memory. And in denying their humanity, we betray our own.

Indifference, then, is not only a sin, it is a punishment.

And this is one of the most important lessons of this outgoing century’s wide-ranging experiments in good and evil.

In the place that I come from, society was composed of three simple categories: the killers, the victims, and the bystanders. During the darkest of times, inside the ghettoes and death camps — and I’m glad that Mrs. Clinton mentioned that we are now commemorating that event, that period, that we are now in the Days of Remembrance — but then, we felt abandoned, forgotten. All of us did.

And our only miserable consolation was that we believed that Auschwitz and Treblinka were closely guarded secrets; that the leaders of the free world did not know what was going on behind those black gates and barbed wire; that they had no knowledge of the war against the Jews that Hitler’s armies and their accomplices waged as part of the war against the Allies. If they knew, we thought, surely those leaders would have moved heaven and earth to intervene. They would have spoken out with great outrage and conviction. They would have bombed the railways leading to Birkenau, just the railways, just once.

And now we knew, we learned, we discovered that the Pentagon knew, the State Department knew. And the illustrious occupant of the White House then, who was a great leader — and I say it with some anguish and pain, because, today is exactly 54 years marking his death — Franklin Delano Roosevelt died on April the 12th, 1945. So he is very much present to me and to us. No doubt, he was a great leader. He mobilized the American people and the world, going into battle, bringing hundreds and thousands of valiant and brave soldiers in America to fight fascism, to fight dictatorship, to fight Hitler. And so many of the young people fell in battle. And, nevertheless, his image in Jewish history — I must say it — his image in Jewish history is flawed.

The depressing tale of the St. Louis is a case in point. Sixty years ago, its human cargo — nearly 1,000 Jews — was turned back to Nazi Germany. And that happened after the Kristallnacht, after the first state sponsored pogrom, with hundreds of Jewish shops destroyed, synagogues burned, thousands of people put in concentration camps. And that ship, which was already in the shores of the United States, was sent back. I don’t understand. Roosevelt was a good man, with a heart. He understood those who needed help.

Why didn’t he allow these refugees to disembark? A thousand people — in America, the great country, the greatest democracy, the most generous of all new nations in modern history. What happened? I don’t understand. Why the indifference, on the highest level, to the suffering of the victims?

But then, there were human beings who were sensitive to our tragedy. Those non-Jews, those Christians, that we call the “Righteous Gentiles,” whose selfless acts of heroism saved the honor of their faith. Why were they so few? Why was there a greater effort to save SS murderers after the war than to save their victims during the war? Why did some of America’s largest corporations continue to do business with Hitler’s Germany until 1942? It has been suggested, and it was documented, that the Wehrmacht could not have conducted its invasion of France without oil obtained from American sources. How is one to explain their indifference?

And yet, my friends, good things have also happened in this traumatic century: the defeat of Nazism, the collapse of communism, the rebirth of Israel on its ancestral soil, the demise of apartheid, Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt, the peace accord in Ireland. And let us remember the meeting, filled with drama and emotion, between Rabin and Arafat that you, Mr. President, convened in this very place. I was here and I will never forget it.

And then, of course, the joint decision of the United States and NATO to intervene in Kosovo and save those victims, those refugees, those who were uprooted by a man, whom I believe that because of his crimes, should be charged with crimes against humanity.

But this time, the world was not silent. This time, we do respond. This time, we intervene.

Does it mean that we have learned from the past? Does it mean that society has changed? Has the human being become less indifferent and more human? Have we really learned from our experiences? Are we less insensitive to the plight of victims of ethnic cleansing and other forms of injustices in places near and far? Is today’s justified intervention in Kosovo, led by you, Mr. President, a lasting warning that never again will the deportation, the terrorization of children and their parents, be allowed anywhere in the world? Will it discourage other dictators in other lands to do the same?

What about the children? Oh, we see them on television, we read about them in the papers, and we do so with a broken heart. Their fate is always the most tragic, inevitably. When adults wage war, children perish. We see their faces, their eyes. Do we hear their pleas? Do we feel their pain, their agony? Every minute one of them dies of disease, violence, famine.

Some of them — so many of them — could be saved.

And so, once again, I think of the young Jewish boy from the Carpathian Mountains. He has accompanied the old man I have become throughout these years of quest and struggle. And together we walk towards the new millennium, carried by profound fear and extraordinary hope.

holocaust

Why We Remember the Holocaust

This video provides an overview of the Holocaust, Days of Remembrance, and why we as a nation remember this history.

Estelle Laughlin, Holocaust Survivor:

Memory is what shapes us. Memory is what teaches us. We must understand that’s where our redemption is.

[Text on screen] Between 1933 and 1945, the German government, led by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, carried out the systematic persecution of and murder of Europe’s Jews. This genocide is now known as the Holocaust. The Nazi regime also persecuted and killed millions of other people it considered politically, racially, or socially unfit. The Allies’ victory ended World War II, but Nazi Germany and its collaborators had left millions dead and countless lives shattered.

Sara Bloomfield, Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

I think the important thing to understand about this cataclysmic event is that it happened in the heart of Europe. Germany was respected around the world for its leading scientists, its physicians, its theologians. It was a very civilized, advanced country. It was a young democracy, but it was a democracy. And yet it descended not only into social collapse but world war and eventually mass murder.

Margit Meissner, Holocaust Survivor:

A strong man came to power in Germany whose ideas were that Germany has to create a national community, which would include only the Aryan race, which he considered superior, and all the people who did not belong to the Aryan race could be eliminated. With planning and propaganda, he was able to convince most of the German people to go along with him, insensitive to what happened to the Jews who had basically been their former neighbors. And he managed to build concentration camps and killing centers and finally gas chambers to annihilate six million Jews and at the same time also millions of others, murdered in a systematic, government-sponsored way.

Raye Farr, Film Curator, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

And it’s made up of so many people who participated in different ways, who made it possible.

Rev. Dr. Chris Leighton, Institute for Christian and Jewish Studies:

People who follow orders without question, bystanders who watch and do nothing, ordinary men and women simply going with the flow.

Raye Farr, Film Curator, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

The events and the results of the Holocaust were so devastating. It was an extreme that we can barely imagine.

Rev. Dr. Chris Leighton, Institute for Christian and Jewish Studies:

It’s so mind-boggling that the temptations to forget and to repress, to just put it out of mind, are very real.

Raye Farr, Film Curator, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

But we remember. We remember because it is an unthinkable scar on humanity. We need to understand what human beings are capable of.

Barack Obama, President of the United States:

We gather today to mourn the loss of so many lives and celebrate those who saved them, honor those who survived, and contemplate the obligations of the living.

Kadian Pow, Museum Educator, Smithsonian Institution:

Days of Remembrance is our nation’s annual commemoration of the Holocaust—this time that was both a blight on the history of humanity but also a shining moment for the people who were brave enough to put an end to it.

Sara Bloomfield, Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

We are remembering, first and foremost, all the victims, and that is not only the Jewish victims, but there were many non-Jewish victims. Of course, the Jews were the primary target.

Estelle Laughlin, Holocaust Survivor:

The millions of innocent people, including my family and friends, who were killed because they were of the wrong religion, because they had no means of protecting themselves.

Sara Bloomfield, Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

It’s also important to remember the rescuers. These were people who risked not only their own lives, sometimes the lives of their family, to save a fellow human being. And we also remember our American soldiers who were fighting to win World War II and in the course of that, liberated these concentration camps.

Col. Michael Underkofler, U.S. Air Force Reserve:

Those that arrived at the camps in 1945 and were just horrified at what they saw.

Carly Gjolaj, Museum Educator, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

And that was a huge task for the American soldiers: to help bring humanity back to these people who had been dehumanized for years, to give them medical care.

Lt. Col. Terrance Sanders, U.S. Army:

Looking back allows us to understand how important it is for us to serve in a country where we have the strength and the might and the will to defend those that are defenseless.

Rabbi M. Bruce Lustig, Washington Hebrew Congregation:

So Days of Remembrance is an opportunity for us to remember the suffering that was and the efforts that were made to put an end to such suffering, and it’s a call to conscience today in our world to make sure that we aren’t the silent ones standing by, contributing to the suffering of others.

Margit Meissner, Holocaust Survivor:

In 1945, at the end of the war, I would have thought that there would never be another Holocaust, that the world was so shocked by what had happened that the world would not permit that. And yet you see what happened in Bosnia, what happened in Rwanda, what happened in Darfur. So there’s still millions of people being persecuted because of their ethnicity.

Sara Bloomfield, Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

It’s really a moral challenge to us to do more in our own lives when we confront injustice or hatred or genocide.

Bridget Conley-Zilkic, Genocide Prevention Educator, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum:

Those who suffered and died in the Holocaust, we can honor them today by not being silent. Remembering ties the past and the present together with a powerful, simple thread: “This is not right.”

Margit Meissner, Holocaust Survivor:

The important thing is that one should not become indifferent to the suffering of others, that one should not stand by and just raise one’s hands and say, “There’s nothing I can do, I’m just a little one person,” because I think what everyone of us does matters.

Estelle Laughlin, Holocaust Survivor:

That’s not enough to curse the darkness of the past. Above all, we have to illuminate the future. And I think that on the Day of Remembrance the most important thing is to remember the humanity that is in all of us to leave the world better for our children and for posterity.

holocaust

The Ten Stages of Genocide By Dr. Gregory H. Stanton

The Ten Stages of Genocide By Dr. Gregory H. Stanton

Racism

How to Make this Moment the Turning Point for Real Change by Barack Obama

How to Make this Moment the Turning Point for Real Change by Barack Obama

June 1, 2020

As millions of people across the country take to the streets and raise their voices in response to the killing of George Floyd and the ongoing problem of unequal justice, many people have reached out asking how we can sustain momentum to bring about real change.

Ultimately, it’s going to be up to a new generation of activists to shape strategies that best fit the times. But I believe there are some basic lessons to draw from past efforts that are worth remembering.

First, the waves of protests across the country represent a genuine and legitimate frustration over a decades-long failure to reform police practices and the broader criminal justice system in the United States. The overwhelming majority of participants have been peaceful, courageous, responsible, and inspiring. They deserve our respect and support, not condemnation — something that police in cities like Camden and Flint have commendably understood.

On the other hand, the small minority of folks who’ve resorted to violence in various forms, whether out of genuine anger or mere opportunism, are putting innocent people at risk, compounding the destruction of neighborhoods that are often already short on services and investment and detracting from the larger cause. I saw an elderly black woman being interviewed today in tears because the only grocery store in her neighborhood had been trashed. If history is any guide, that store may take years to come back. So let’s not excuse violence, or rationalize it, or participate in it. If we want our criminal justice system, and American society at large, to operate on a higher ethical code, then we have to model that code ourselves.

Second, I’ve heard some suggest that the recurrent problem of racial bias in our criminal justice system proves that only protests and direct action can bring about change, and that voting and participation in electoral politics is a waste of time. I couldn’t disagree more. The point of protest is to raise public awareness, to put a spotlight on injustice, and to make the powers that be uncomfortable; in fact, throughout American history, it’s often only been in response to protests and civil disobedience that the political system has even paid attention to marginalized communities. But eventually, aspirations have to be translated into specific laws and institutional practices — and in a democracy, that only happens when we elect government officials who are responsive to our demands.

Moreover, it’s important for us to understand which levels of government have the biggest impact on our criminal justice system and police practices. When we think about politics, a lot of us focus only on the presidency and the federal government. And yes, we should be fighting to make sure that we have a president, a Congress, a U.S. Justice Department, and a federal judiciary that actually recognize the ongoing, corrosive role that racism plays in our society and want to do something about it. But the elected officials who matter most in reforming police departments and the criminal justice system work at the state and local levels.

It’s mayors and county executives that appoint most police chiefs and negotiate collective bargaining agreements with police unions. It’s district attorneys and state’s attorneys that decide whether or not to investigate and ultimately charge those involved in police misconduct. Those are all elected positions. In some places, police review boards with the power to monitor police conduct are elected as well. Unfortunately, voter turnout in these local races is usually pitifully low, especially among young people — which makes no sense given the direct impact these offices have on social justice issues, not to mention the fact that who wins and who loses those seats is often determined by just a few thousand, or even a few hundred, votes.

So the bottom line is this: if we want to bring about real change, then the choice isn’t between protest and politics. We have to do both. We have to mobilize to raise awareness, and we have to organize and cast our ballots to make sure that we elect candidates who will act on reform.

Finally, the more specific we can make demands for criminal justice and police reform, the harder it will be for elected officials to just offer lip service to the cause and then fall back into business as usual once protests have gone away. The content of that reform agenda will be different for various communities. A big city may need one set of reforms; a rural community may need another. Some agencies will require wholesale rehabilitation; others should make minor improvements. Every law enforcement agency should have clear policies, including an independent body that conducts investigations of alleged misconduct. Tailoring reforms for each community will require local activists and organizations to do their research and educate fellow citizens in their community on what strategies work best.

But as a starting point, here’s a report and toolkit developed by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and based on the work of the Task Force on 21st Century Policing that I formed when I was in the White House. And if you’re interested in taking concrete action, we’ve also created a dedicated site at the Obama Foundation to aggregate and direct you to useful resources and organizations who’ve been fighting the good fight at the local and national levels for years.

I recognize that these past few months have been hard and dispiriting — that the fear, sorrow, uncertainty, and hardship of a pandemic have been compounded by tragic reminders that prejudice and inequality still shape so much of American life. But watching the heightened activism of young people in recent weeks, of every race and every station, makes me hopeful. If, going forward, we can channel our justifiable anger into peaceful, sustained, and effective action, then this moment can be a real turning point in our nation’s long journey to live up to our highest ideals.

Let’s get to work.

Racism

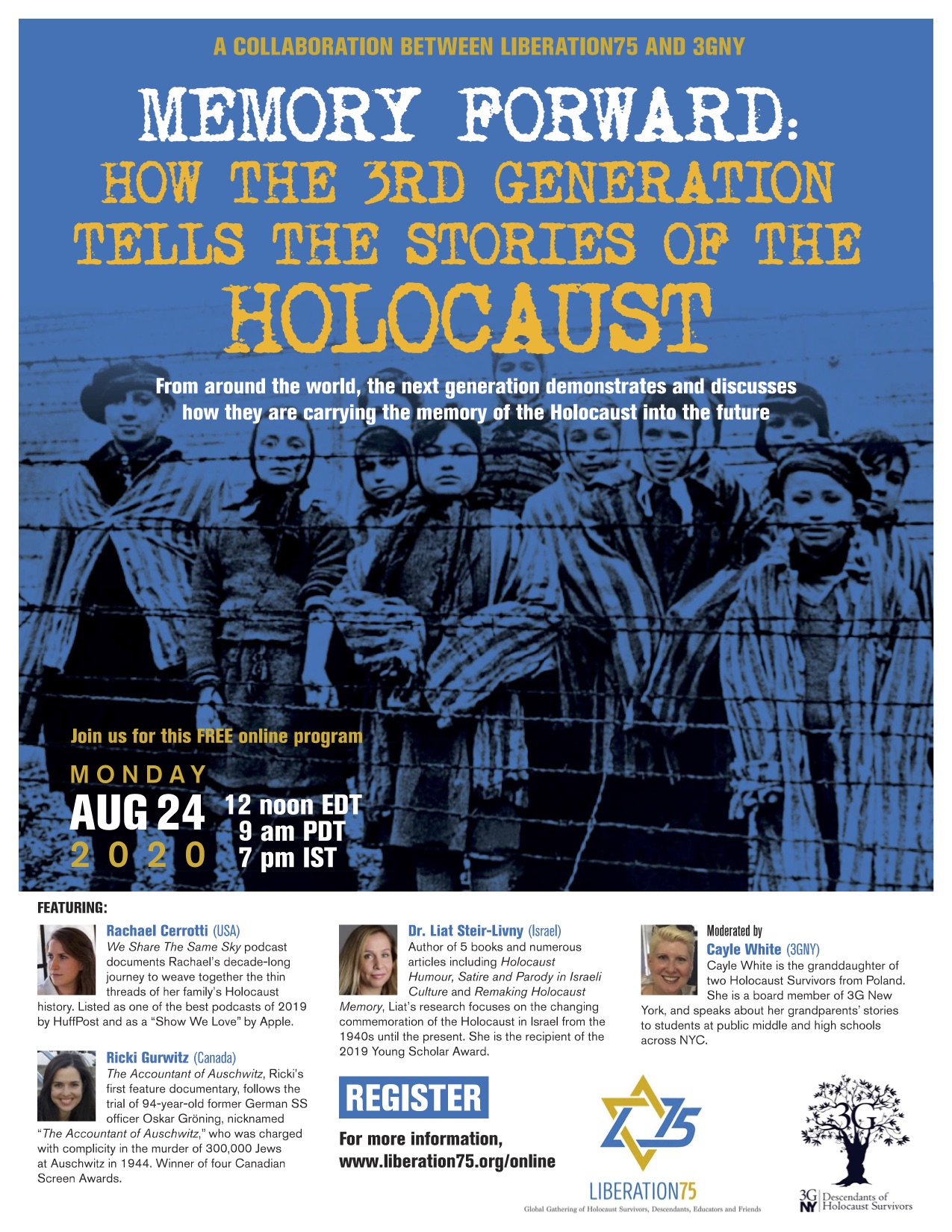

Peonage as Systemic Racism by Damon K. Roberts

In 1866, one year after the 13 Amendment was ratified (the amendment that ended slavery), Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, and South Carolina began to lease out convicts for labor (peonage). This made the business of arresting Blacks very lucrative, which is why hundreds of White men were hired by these states as police officers. Their primary responsibility was to search out and arrest Blacks who were in violation of Black Codes. Once arrested, these men, women and children would be leased to plantations where they would harvest cotton, tobacco, sugar cane. Or they would be leased to work at coal mines, or railroad companies. The owners of these businesses would pay the state for every prisoner who worked for them; prison labor.

It is believed that after the passing of the 13th Amendment, more than 800,000 Blacks were part of the system of peonage, or re-enslavement through the prison system. Peonage didn’t end until after World War II began, around 1940.

This is how it happened.

The 13th Amendment declared that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” (Ratified in 1865)

Did you catch that? It says, “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude could occur except as a punishment for a crime.” Lawmakers used this phrase to make petty offenses crimes. When Blacks were found guilty of committing these crimes, they were imprisoned and then leased out to the same businesses that lost slaves after the passing of the 13th Amendment. This system of convict labor is called peonage.

The majority of White Southern farmers and business owners hated the 13th Amendment because it took away slave labor. As a way to appease them, the federal government turned a blind eye when southern states used this clause in the 13th Amendment to establish laws called Black Codes.

Here are some examples of Black Codes:

In Louisiana, it was illegal for a Black man to preach to Black congregations without special permission in writing from the president of the police. If caught, he could be arrested and fined. If he could not pay the fines, which were unbelievably high, he would be forced to work for an individual, or go to jail or prison where he would work until his debt was paid off. If a Black person did not have a job, he or she could be arrested and imprisoned on the charge of vagrancy or loitering.

This next Black Code will make you cringe. In South Carolina, if the parent of a Black child was considered vagrant, the judicial system allowed the police and/or other government agencies to “apprentice” the child to an “employer”. Males could be held until the age of 21, and females could be held until they were 18. Their owner had the legal right to inflict punishment on the child for disobedience, and to recapture them if they ran away.

This (peonage) is an example of systemic racism – Racism established and perpetuated by government systems. Slavery was made legal by the U.S. Government. Segregation, Black Codes, Jim Crow and peonage were all made legal by the government, and upheld by the judicial system. These acts of racism were built into the system, which is where the term “Systemic Racism” is derived.