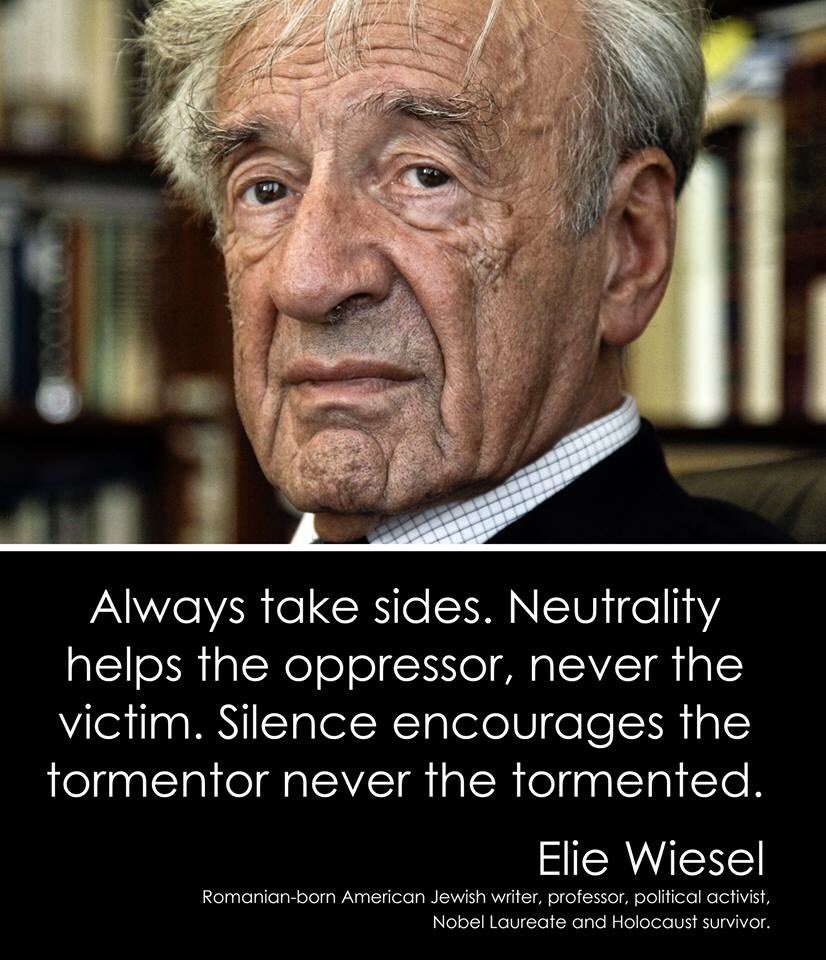

holocaust

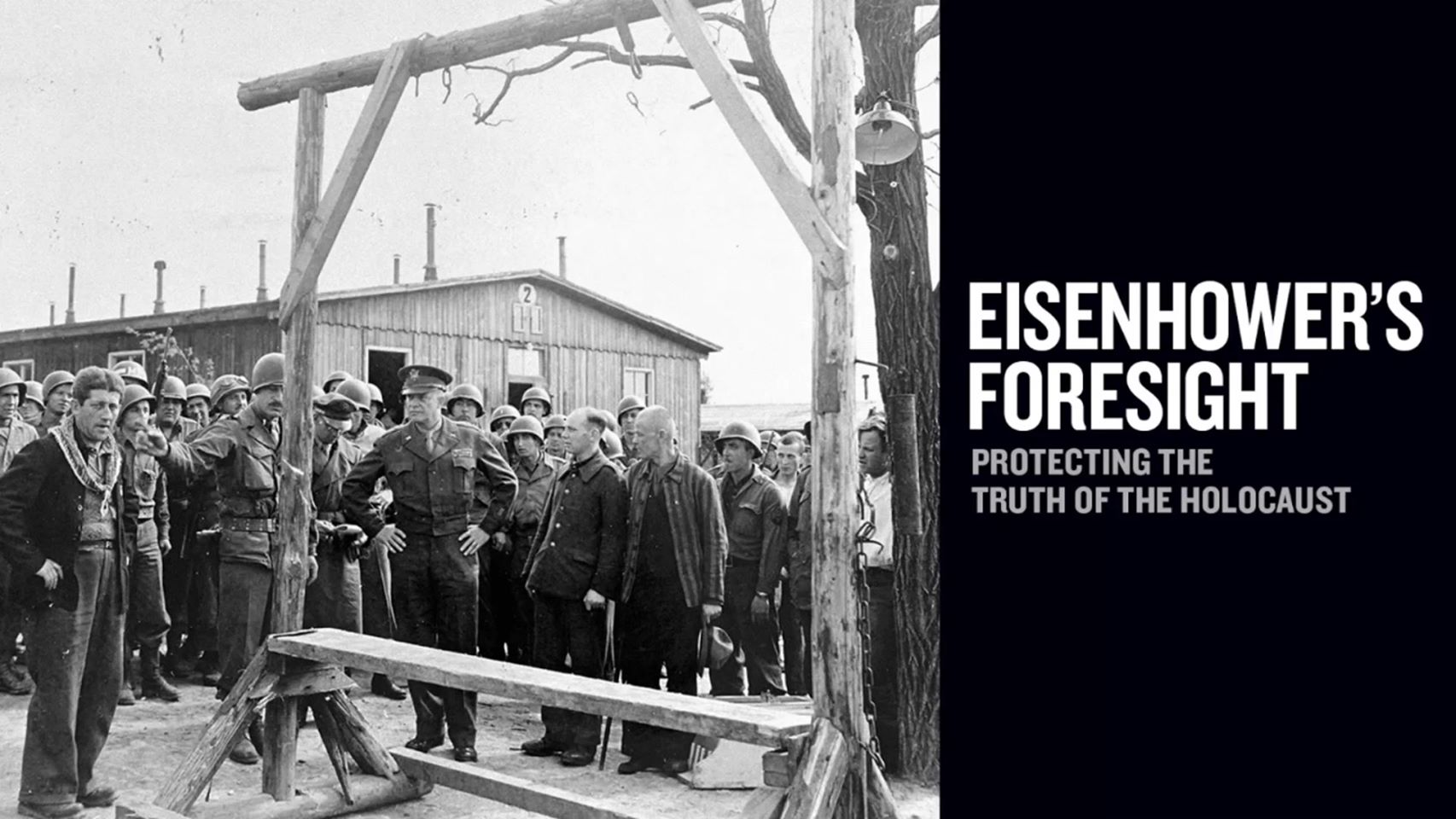

Eisenhower’s Foresight: Protecting the Truth of the Holocaust

While Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower had studied his World War II enemy, he was unprepared for the Nazi brutality he witnessed at Ohrdruf concentration camp in April 1945. Bodies were piled like wood and living skeletons struggled to survive. On International Holocaust Remembrance Day, learn how Eisenhower foresaw Read more…