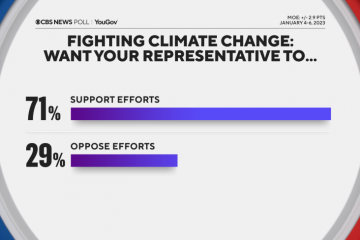

Climate Change

CBS News poll analysis: Amid concern about extreme weather events, most want Congress to fight climate change

Author: CBS News URL: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/extreme-weather-opinion-poll-2023-1-10/ As Americans look ahead, more than half are pessimistic about the prospect of extreme weather events and climate, particularly those who report having faced more extreme weather in their local area in recent years. They say this experience with extreme weather has led them to Read more…